Satoshi Ikeuchi, Professor, Religion and Global Security, University of Tokyo

In the Eastern Mediterranean region, the game of chess is being played by regional and external powers. Fundamentally, the main players are Turkey and Israel. Egypt, UAE, Greece and Cyprus are also involved partially. Russia recently joined and increasingly important, with dubious sincerity, though.

On November 27 last year, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan stuck controversial deals with Libya’s internationally recognized Government of National Accord (GNA) in Tripoli, led by Prime Minister Fayez al-Sarraj.

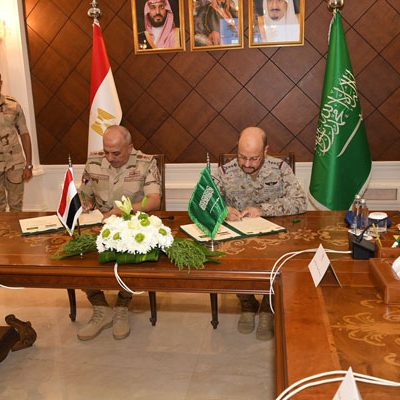

In one of the agreements signed on that day, Turkey was given a right to deploy military forces to train and advise Tripoli government troops for a wide range of purposes.

In conjunction with or in exchange for that, Erdogan extracted an extraordinary agreement from al-Sarraj on maritime boundary which has implications on the wider East Mediterranean affairs.

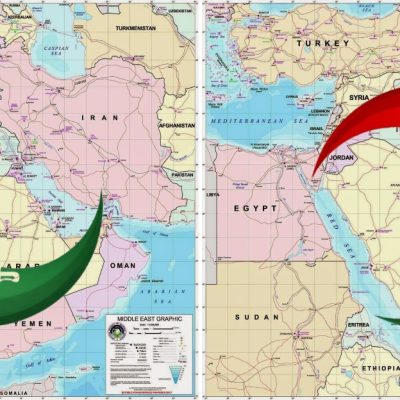

The Turkey-Libya Maritime Boundary Delimitation Agreement declared to have established continental shelf limits and exclusive economic zones (EEZs) within maritime zones between two countries. The agreement effectively claimed that Turkey and Libya together have a maritime exclusive zone over and across the Mediterranean Sea blocking any economic exploration such as exploring offshore oil fields and laying pipelines.

Of course, this was an agreement which almost nobody approves of, except fot the two signatories.

Obviously, it was a move of chess in an attempt to disrupt the EastMed Pipeline Project, led by Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu.

On January 2, 2020, Netanyahu flew to Athens to sign an agreement with Greece and Cyprus to great fanfare, on the pipeline project to deliver natural gas off the coast of Cyprus via Crete Island, Peloponnese Peninsula and Italy to the western European consumers.

Again, as with the agreement between Turkey and Libya, feasibility of this project is obscure. Technically, economically and politically, there are full of difficulties.

The fundamental question is whether the Eastern Mediterranean gas field is of such scale and capacity. Israel also started to send raw gas from Leviathan gas field to Egypt on January 15 this year.

This will strengthen Israel’s strategic relationship with Egypt. Egypt will fill the gap in its immediate energy needs and soon reactivate facilities to process the gas and reexport it as LNG to other consumers possibly in the western Europe, becoming an energy transit state. It’s a strategic gain for the moment.

But if the EastMed Pipeline miraculously succeeds, then will there still be gas left for Egypt? By showing rosy pictures simultaneously to Greece and Egypt, Netanyahu might be trying to kill two birds with one stone, or running after two hares, eventually catching neither.