Satoshi Ikeuchi, Professor, Religion and Global Security, University of Tokyo.

President Trump declared victory in a televised speech on Sunday morning, October 27 announcing the death of Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, the leader of the Islamic State militant group, also called derogatively Daesh in Arabic, during a raid by the U.S. Special Forces in the previous night.

The Islamic State confirmed this in an audio message released through its affiliated media outlet al-Furqan on October 31. In this recorded message, alleged new spokesman by the name of Abu Hamza al-Qurashi announced the appointment of Abu Ibrahim al-Hashimi al-Qurashi as the group’s new leader.

So, the story goes on.

The IS in Iraq and Syria has already been gone, at least for the most part. Still, its lure in the mind of alienated youths in societies all over the world remains although to the lesser extent.

The IS has two faces. One is a quasi-state with territorial entity under their rule. The IS as a state thrives in the context of deep ethnic divisions or widespread mistrust in the society, as well as malfunctioning of central governments and neglect or even tacit helps by regional and external powers. If domestic governments become more functional and cooperate with regional and super-powers, the IS territorial rule can’t be sustained long.

The other face is the ideology by which voluntary acts of violence are instigated among the disgruntled young Muslims. Islamic jurisprudence, by its nature and structure of de-centrality, tends to be susceptible to de-centralized mobilization by militants who call for spontaneous acts of terror in the name of pious Jihad. Even if the number of people who take up arms in response to such calls, in global context and in an aggregate number, there are a large mass of people who forms “flash mobs” and mushrooms in various circumstances.

It would be helpful to grasp the basic mechanism of the IS as a pendulum’s swing between these two poles: the IS as a territorial entity and the IS as an ideology.

Now the IS territory is almost obliterated from Iraq and Syria, the pendulum swings to the far side, almost solely as an ideology. But it is not permanent.

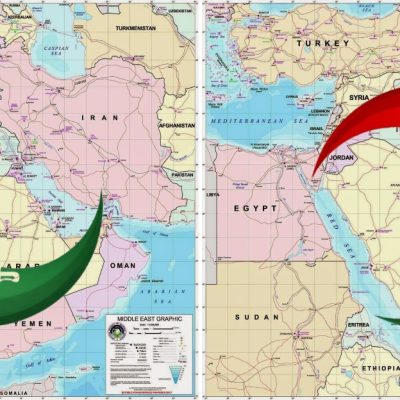

Power-vacuum caused by the regional power rivalry which emanates from Iran’s rise as a hegemonic power may again turn the swing of the pendulum towards the other end. The unconcealed intention by the U.S. president in favor of keeping away from the conflict in the Middle East might accelerate this movement back.