On the surface, the conflict in Sudan appears to be between a regular army and a rebel force that has broken away from its authority. However, the reality is far deeper than this dichotomy. The war tearing Sudan apart is not merely a power struggle; it is a battle within the very structure of political Islam itself, between a faction that has lost control of its instruments (the Rapid Support Forces) and another faction seeking to regain power under the banner of the “National Army.”

First: From Religious Exploitation to the Militarization of the Islamist Project

From the era of Jaafar Nimeiri, when religion began to be used in politics, until Omar al-Bashir’s coup in 1989, Sudan never strayed from the orbit of political Islam. The Sudanese Islamist movement (known locally as the Islamists) succeeded where similar movements in other Arab countries failed:

Infiltrating the army and the state not as an adversary, but as an integral part of them.

The military institution itself was religiously indoctrinated, its loyalty shifted from the state to the “Islamic project.” Sudanese officers were raised to believe that “the army is the arm of the call to Islam,” and that protecting the Islamic regime superseded protecting the constitution.

Therefore, when al-Bashir staged his coup, it was not merely a military coup, but the culmination of a long process of ideological indoctrination of the military institution.

Thus, the army was transformed into an ideological tool cloaked in nationalist garb, while the concept of a unified state eroded in favor of a closed, religiously-based partisan project.

Second: The Rapid Support Forces as an illegitimate offspring of the movement

When the Darfur crisis erupted, the regime used tribal militias as an internal weapon to protect its center of power, creating what later became known as the Rapid Support Forces.

These forces were a direct product of the Islamists’ policy in managing the civil conflict:

Utilizing tribalism, distributing weapons, and linking loyalty to both religion and money.

But what the Islamists failed to realize was that this tool would, over time, transform into a parallel power to the state, possessing its own logic and independent resources, until it spiraled out of control and inherited a portion of power and legitimacy by virtue of its military might.

Thus, the current war is not between two opposing projects, but rather between a father who has lost his authority and his rebellious son.

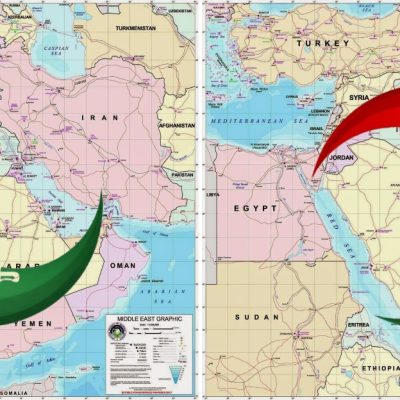

Third: Why isn’t Chad accused, despite being the de facto corridor?

Geographical logic dictates that any external support for the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) passes through the western border with Chad, where tribal entanglements and open roads abound.

However, Burhan doesn’t dare accuse N’Djamena for several reasons:

1. Accusing Chad would threaten a fragile tribal balance within Darfur, a balance that could explode in his face.

2. The Chadian regime enjoys increasing Russian support following the decline of the French presence, and Burhan doesn’t want to antagonize Moscow, which provides him with political and military support.

3. Chad acts as a buffer zone, preventing the war from spreading deeper into Africa, a danger Burhan is well aware of. Therefore, Burhan remained silent about the nearby neighbor and directed his accusation at the distant one.

Fourth: The UAE as a Ready-Made Ideological Enemy

The insistence of the official and pro-Burhan media discourse on accusing the UAE is not innocent; the campaign serves two objectives:

Politically: to divert attention from the army’s failures to achieve a decisive victory and to justify the continuation of the war under the pretext of “foreign intervention.”

Ideologically: to remobilize the Islamist movement under the banner of “confronting the secular Arab alliance,” which justifies the return of the Islamists to the political scene under the banner of “defending the army and religion.”

In the Islamists’ consciousness, the UAE represents a symbol opposed to their historical project, thus making it easy to transform into the “declared enemy” that unites the ranks and justifies the mobilization rhetoric.

Fifth: Egyptian Ambiguity

Many voices in Egypt, sometimes with good intentions, treat the Sudanese army as if it were similar to the Egyptian army in terms of its structure and the patriotism of its role, while the difference is fundamental. After three decades of al-Bashir’s rule, the Sudanese army is no longer a purely national institution, but rather a hybrid structure where religious, tribal, and organizational loyalties intersect.

This is the source of the misunderstanding: when some Egyptians support Burhan, they believe they are supporting the “Sudanese state,” while in reality, they are supporting a political extension of the Islamist movement, which has lost its overt influence and is seeking a disguised comeback through the military establishment.

Sixth: Between the Army’s Discourse and the Movement’s Reality

Burhan today does not rule in the name of the state, but rather in the name of a narrative of defending the state.

The Islamists, for their part, use this discourse to portray themselves as guardians of Islamic identity against foreign conspiracies, exploiting a misguided Arab consciousness and a short political memory.

In the background, religion, the army, and tribalism continue to be used as a single weapon to prolong the life of a regime that has lost its moral legitimacy but still clings to the reins of power.

Seventh: Towards a More Accurate Understanding of the Sudanese Predicament

The essence of the Sudanese crisis lies not in the multiplicity of armies, nor in the conflict among generals, but rather in the inability of political Islam to transform into a state project after exhausting all its tools.

It is now reproducing itself as a “state of the faithful army,” after failing to establish a state based on Sharia law and proselytizing.

If the Rapid Support Forces revealed the armed face of al-Bashir’s old policies, then Burhan is today revealing its new institutional—and legitimate—face, in military uniforms and with national slogans, but concealing the same structure.

Conclusion: When Ideology Disguises Itself in Military Uniform

The accusations against the UAE and Khartoum’s silence regarding Chad and Russia are merely a reflection of ideological alignment rather than pragmatic considerations.

Burhan and his Islamist allies are fighting a battle for survival, not in the name of Sudan, but in the name of an ideology that sees the army as its last bastion after the collapse of the project in politics and society. Therefore, what is happening in Sudan today is not merely a war between an army and a militia, but a war over the very identity of the state:

Will it remain captive to a politicized, exclusionary religious discourse hiding behind the gun, or will it break free from the shackles of the past and move towards a civil state that accepts and embraces diversity, reclaiming its right to exist without ideological intermediaries?

By: Major General Yasser Hashem

Head of the Security & Military Department

Institute for Global Security & Defense Affairs