Col. (GS) Eric Michiels, Defense Attaché of Belgium, NATO and EU to GCC countries, Abu Dhabi

U-Tokyo (ROLES & IGSDA) 2nd Seminar on 12 February 2021

The Mediterranean, the natural border of Southern Europe. As such, the Mediterranean is a de facto security issue between Europe and the countries bordering it. From a geographical and geostrategic point of view, the eastern part of the Mediterranean represents a major challenge because it is the gateway to the East in more than one respect. The area is the cradle of various conflicts and inter-state tensions.

In this paper, we will first address the specificities of the union and its interests. Then we will look at the various hotbeds of tension in the region, but limiting ourselves to a European perspective, which does not mean that this will be the European perspective or vision.

- The meaning of the Union in the European Union

Europe is not a sovereign and united entity of 27 states in the same sense that we have the 50 states that make up the United States of America.

Europe only imposes its views on its members in matters for which the member states have agreed.

Each state remains sovereign and decisions at European level are taken unanimously.

In order to highlight one of the specificities of the European Union, we can take legislation. If we talk about European legislation, each member state has to translate the rules into its own law.

The European Union has the will to act in an orderly way, with one voice. And it can do so in everything that is in the common interest…of the 27 countries. It is easy to understand that finding convergence among the 27 is relatively difficult when we do not necessarily share the same language, the same culture, the same history and when interests are therefore sometimes divergent.

Consensus is often reached on the lowest common denominator, which means that the voice, the position of the European Union often seems so weak, because it has first been attenuated internally.

If we are talking about foreign and external security policy where the interests of a country like France, sitting as a permanent member of the UN Security Council, with a strong colonial past, an industry open to exports,…cannot always be in line with the interests of a small country like Luxembourg, or a Nordic country like Sweden, or a neighbour of Russia like Poland.

So when it comes to interests, especially economic interests, sovereignty, most member states go it alone, certainly when it comes to everything outside Europe.

The complexity of the institution, with a presidency held successively by the member states for periods of six months, has certainly not helped to make the voice of the European Union heard.

Fortunately, Europe is getting organised, and since the Treaty of Lisbon adopted in 2009, a High Representative for Foreign Affairs has been in place. This gives a better visibility but also ensures consistency in the longer term. This Super Foreign Minister represents the voice of the 27 foreign ministers of the members of the Union but also has his own prerogatives. However, it should be noted that it is not the function that makes the man, but the opposite, and progress is directly dependent on the stature of the person occupying the post. And the fact remains that he must make the link with the policy of the 27 member states and cannot develop his own.

One of the signs that this function has certain weaknesses is the appearance in 2006 of the European Troika or commonly known as the E3. This is the informal grouping of the three main powers within the union, namely Germany, France and the United Kingdom, which act together to defend the European position . This trio was involved for the first time in the negotiations on the Iranian JCPOA agreement. Even after the creation of the post of High Representative for Foreign Affairs in 2009, the E3 has continued to do business on behalf of the European Union, but maybe more for internal affairs. What will be the future of this trio where the United Kingdom will be replaced by Italy since Brexit and what will be the remaining weight of this de facto association?

If the formula has shown its interest, it has above all demonstrated the lack of influence or recognition of the Foreign Affairs pillar within the European institution.

It must be said that when it comes to action outside Europe, it is above all the particular interests of each of its members that prevail. They are moving forward in a dispersed order and we can find members of the union in direct conflict of interest in certain dossiers: Italian and French interests can be divergent on the Libyan dossier, French and German points of view diverge with regard to migration and the attitude towards Turkey.

- What are the areas in which the European Union takes joint action?

Focusing on external action and looking at the different power factors, European action can be summarised as follows:

In the field of the economy, European action is mainly in the field of legislation, the enactment of standards, the regulation of competition. As such, it concludes trade treaties with the major players in the world, with varying degrees of success, if we take into account, for example, the CETA Agreement between the European Union and Canada. It therefore regulates trade agreements with trading partners outside Europe, such as Russia and Turkey, but also, more currently, with the United Kingdom. One of the pressure points is generally the application of customs tariffs, but also the delimitation of fishing zones with the neighbouring states of the union (a great challenge for Brexit), quotas but also health standards for food imports and exports. Finally, Europe still has a marvellous economic sanctions tool that is relatively powerful and effective, as soon as the consensus to use it is reached.

In the political field, the action of the Union is rather…internal. It must first of all, for each problem, find the consensus between its member states, and this monopolises all its time. Following the European elections of 2019, the member states have devoted their time to finding senior officials, whereas there was an emergency with the Syrian crisis, the Turkish intervention, the tensions in Hong Kong and global warming. The Brexit crisis also mobilised many resources. However, it must be recognised that the tool of “European membership” can also be a tool of pressure or seduction. We must also recognise that the European Union is a master in the defence of human rights, democracy and equality between men and women. These values (and not interests) are part of the talking points of every politician and diplomat of the member states when they are on mission or posted abroad.

Finally, in the field of security, there is indeed a Europe of Defence, but there is not yet a European Defence. There is cooperation and coordination, but there is no common military action at European level, except at sea, certainly in regions of tension such as Syria. In the field of security, Europe has concerted action for the control of external borders and even has a dedicated agency for this: FRONTEX. Linked to the securing of borders is the problem of migration. This last problem is certainly the one that most worries the European Union for its security and which is the most debated internally. The migratory aspect is a determining factor in the relations between the Union and its Eastern Mediterranean neighbours.

Terrorism is one of the security issues that motivates European action.

- Security action by the European Union

In order to preserve its borders, prevent migration flows and protect itself from terrorism, the action of the Union’s External Service can take different forms.

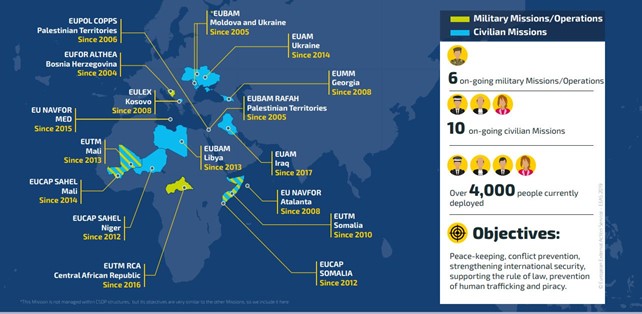

First of all, “Civilian” missions, which aim to assist countries in order to preserve stability. From a “force” point of view, these are mainly police missions.

On the military side, the Union is mainly involved in training and education missions: the EUTM (European Union Training mission) missions such as in MALI.

The more robust side of the use of force at the level of the European Union is in its action at sea, and more particularly in the Mediterranean Sea, with the EUNAVFOR MED “IRINI” operation.

- The migration problem

The issue of migration is a multifaceted one. It is both a security issue, because in the event of uncontrolled flows, it can destabilise states. But it is also economic, because for some countries, such as Germany, migration is one of the means of maintaining population growth and therefore labour force growth. As such, migration is sometimes a solution and not a problem. The most surprising thing is that the European states with the greatest demographic deficit are those that are the most reluctant to accept migration…because they are the most economically fragile states and therefore where populism is most present. Finally, the problem of migration is an internal issue for all the member states where the populations, in the context of the economic crisis, see it as a threat. It becomes a source of division between the states of the union. With the Syrian crisis, the European Union has experienced serious blockages between member states following disagreements on the repartition of refugees within the Union.

Not controlled immigration comes mainly via three countries: Spain, Italy and Greece. So via the Mediterranean routes. From 2014 to 2019, 60% of migrants came via Greece. The second gateway is Italy. The number of refugees has drastically decreased in recent years for two reasons: an agreement with Turkey and a military presence off the coast of Libya.

The migration problem is therefore an internal issue for the European Union but also a problem of international tensions between Greece and Turkey on the one hand and between Italy and Libya on the other.

Athens, tired of having to shoulder the burden of immigrants entering Europe through its territory, is now taking a hard line, even if it means closing part of its common border with Turkey to asylum seekers, despite the international conventions that Greece has signed. For his part, in March 2020, dissatisfied with the criticism of the European Union during its offensive against the Kurds in northern Syria, the Turkish president announced the opening of its borders to migrants wishing to join Europe, despite the agreement on immigration control that he signed with Brussels in March 2016. This controversial agreement had been negotiated by Angela Merkel on behalf of the European Union. Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan agreed to increase patrols at sea and to receive asylum seekers who arrived in Greece after the agreements were signed. In exchange, for each Syrian migrant sent back to Turkey from the Greek islands, the Union undertook to resettle in Europe a Syrian living in a Turkish refugee camp. Brussels would provide €6bn in aid for the 2.7m Syrian refugees in Turkey. It also promised to reopen negotiations on Turkey’s accession and, more importantly from Ankara’s point of view, to offer its citizens the possibility of visa-free travel to Europe.

The migration problem is a complex issue which is latent in all the discussions between Turkey and the Union but also between Turkey and Greece.

- The hotbeds of tension in the Eastern Mediterranean

In addition to the problem of migration, which is a major challenge for the stability of the Union, there are tensions between the European Union, or some of its Member States, and regional actors. So we will consider the relations with Turkey, Russia and finally the particular case of Libya. There are, of course, other areas of tension such as relations between Israel and Lebanon, but these will not be discussed in this paper because they are less directly related to Europe.

- Conflictual relations with Turkey

- Cypriot disputes

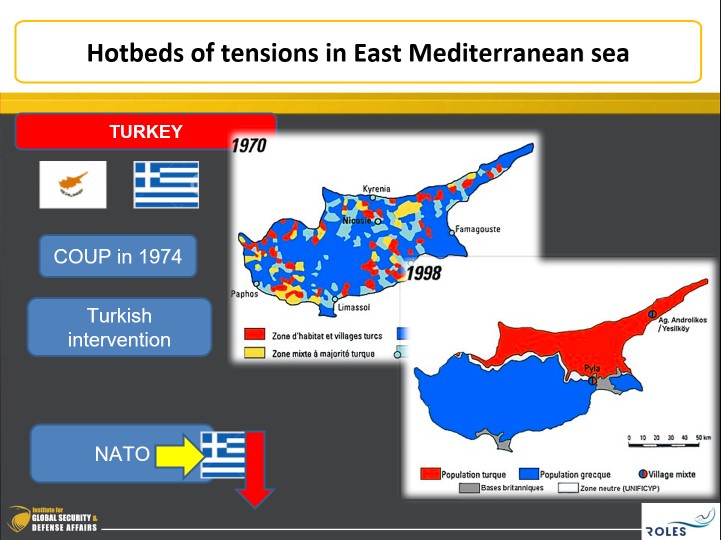

Cyprus has been a member of the European Union since 2004. It became independent from the United Kingdom in 1960. It was 82% Greek Cypriot and 18% Turkish Cypriot. At the time of independence, a treaty was signed between the United Kingdom, Greece and Turkey giving each the right of military intervention to guarantee and restore the constitutional order if it were to be violated.

During the period of the dictatorship of the Colonels in Greece, the National Guard led by Greek officers attempted a coup d’état against the Cypriot president with the aim of unifying the island and attaching it to Greece. On 20 July 1974, the Turks intervened to safeguard the interests of the Turkish community. The UN called for the withdrawal of all troops and Turkey invoked the treaty in order to legitimise its intervention and also to avoid direct confrontation with Greece, which was part of NATO.

Greece had come close to a conflict with Turkey. NATO asked Greece to withdraw all its officers from Cyprus. Greece then withdrew from NATO and did not rejoin it until 1980, after the Turkish veto was lifted.

- Maritime borders and exclusive economic zones

Some Greek islands were ceded by Italy at the end of World War II. Some of them practically touch Turkey. Under the 1947 Treaty of Paris, these islands should be demilitarised. This is not the case since Greece has been watching Turkey from these shores since the invasion of Cyprus in 1974. This defence was strengthened following the 1996 Greek-Turkish crisis over the Imia islands.

Turkey contests Greek sovereignty over several islands, islets and rocks along its coast. Above all, it is one of the few countries, along with the United States, that has not signed the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (known as the Montego Bay Convention, which entered into force in 1994), and does not recognise Greece’s claim to a continental shelf around its islands.

The international rule for the territorial waters is 12 miles from the coasts but only 6 miles between Greece and Turkey. If it was 12 miles, Turkey would no longer be able to cross the Aegean Sea due to the presence of a large number of Greeks islands.

Moreover, the dispute also concerns the EEZ (exclusive economic zone) which is 200 miles. For Turkey, the EEZ does not exist if Greece only claims its 6-mile limit. It therefore wants an EEZ which includes certain Greeks islands.

So close to Turkey, the island of Kastellorizo is 120 kilometres from the first other Greek island – Rhodes – and more than 520 kilometres from the Greek mainland. While most of the Aegean Sea could be claimed by Athens as an Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) under the Montego Bay Convention, this remote island of nine square kilometres gives it a de facto large extension of several hundred square kilometres in the Eastern Mediterranean, as far as Cyprus. However, in the absence of a bilateral agreement, Ankara claims to have free access to it, especially since the discovery of potentially exploitable hydrocarbon deposits in the Eastern Mediterranean.

Tensions peaked in the summer of 2020 when Turkey sent the Oruç Reis, an exploration ship, into the Greek area.

Ankara argues also that the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC), recognised by Turkey alone, should be given its own EEZ, which further reduces that of the Republic of Cyprus, in addition to claiming part of the Cypriot EEZ. Turkey had already deployed three drill ships in Cyprus waters.

Turkey is anxious to guarantee the Turkish Cypriots a share of future gas revenues and to free Turkey from its dependence on Russian gas supplies.

In the race for the appropriation of maritime zones, Recep Tayyip Erdogan and the head of the Government of National Accord (GAN), Faïez Sarraj, also concluded on 27 November 2019 an agreement delimiting their EEZs, granting Ankara rights over a vast area largely claimed by Greece. The text delimits a 35-kilometre line that will form a maritime border from the southwest coast of Turkey to the north of Libya, and crosses the areas claimed by Greece and Cyprus. It disrupts the planned route of the 1,900 kilometre EastMed pipeline that would carry gas from Israel through Cyprus and Greece to southern Europe. EastMed would enable Greece to become an important energy player and compete with the gas pipelines transiting through Turkey.

Greece called on the UN Security Council and NATO to condemn Turkey’s maritime agreement and expelled the Libyan ambassador to Greece because of it.

The EU countries have so far had difficulty in adopting joint declarations against Turkey. France, which has had difficult relations with Ankara for several years, which have deteriorated further since their opposition in the Libyan conflict, announced on 13 August that it was sending two Rafale and two naval vessels to support Greece.

On 10 September, France, Greece, Italy, Spain, Cyprus, Malta (the so-called Med-7) and Portugal warned Turkey that the EU would be ready to take sanctions if Ankara did not “put an end to its unilateral activities”. In mid-September, Greece announced the purchase of 18 RAFALE aircraft from France, in appreciation of the support.

But the support of other European countries – particularly Germany – for sanctions against Turkey is difficult to obtain. The 2016 migration pact has a lot to do with this, with Ankara frequently threatening to open its borders to Europe to refugees on its territory. Germany is also Turkey’s largest European trading partner and has a large Turkish community on its territory.

At the end of the European summit on 10 and 11 December, the European Union announced a first round of sanctions against Turkey because of its exploration operations. These measures include visa restrictions and asset freezes for persons linked to the disputed gas exploration in the Mediterranean. Athens called for stronger measures, such as an arms embargo, which didn’t get so far the support of the other EU countries. One of the reason could be the intention of Turkey to acquire six German submarines…

Brussels assures that further measures could fall in March 2021 if Ankara does not stop these “illegal and aggressive” actions.

As last development, after five years of interruption, Turkey and Greece resumed talks on Monday 25 January 2021 on their differences in the Mediterranean.

It should also be noted that Greeks and Turks are once again talking to each other within NATO.

- Russia

Russia does not border the Mediterranean, but the Mediterranean is of strategic importance from a military point of view because it is its gateway out of the Black Sea. The Mediterranean is also NATO’s southern border and Moscow is trying to exert its influence on the contours of the alliance in order to reduce its tendency to expand. Russia is present and involved in the Syrian and Libyan conflicts and is trying to forge alliances with as many countries in the Eastern Mediterranean as possible, such as Egypt.

Mr Vladimir Putin has placed sovereignty at the heart of the power project he is carrying for Russia, to which he wants to restore its status as a leading world player. The success of the Syrian military campaign serves as a multiplier of influence.

Russia is perfectly at ease with “frozen conflicts”. It has already demonstrated this in Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova. This inexpensive mechanism gives it a destabilising influence and, for those three countries, blocks any prospect of accession to the European Union and NATO. For Moscow, opening one more “frozen conflict” in Libya, the time to be granted a certain number of military bases – as was the case in Syria – is a realistic option.

The continuation of a latent war, without victors or defeated, seems to be the option chosen by the Kremlin.

In Libya, a “Syrian-style” situation is therefore emerging with the country divided into zones of influence between Russia and Turkey.

This situation is very disturbing for Europe, which is trying to stabilise its border areas, of which Libya is a part. France, Italy and Germany regularly call on the two countries (Turkey and Russia) to suspend the build-up of military resources throughout the country.

On the economic front, the two huge gas pipelines, Nordstream and Southstream, are key pieces in Russia’s geostrategy to supply gas to the whole of Europe. The Russians joined forces with the Germans, Dutch and French for the construction of the northern gas pipeline, then with the Italians and again with the French and Germans for the southern pipeline.

It is easy to understand that Europe’s hyper-dependence on Russian gas is an advantage that Moscow is using, much to the chagrin of the United States. Putin can afford to ignore calls from Europeans on security issues.

On 4 and 5 February 2021, the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs, Josep Borrell, visited Moscow to discuss the various disputes with Russia, of which there are many: Ukraine, Belarus, Georgia, Nagorno Karabagh, the Syrian and Libyan crises, but also human rights and the treatment accorded to Putin’s main opponent, Mr Navalny, who was presumably poisoned and now imprisoned. The European High Representative has been ignored by Lavrov. Only the aspect that Sputnik V could be selected as a vaccine for the European Union caught his attention. During this visit, Russia announced the expulsion of three European diplomats (Germany, Poland, Sweden) for taking a stance on the Navalny affair. These three countries have each just expelled a Russian diplomat. The EU is expected to discuss sanctions against Russia at the meeting on 22 February.

- Russo-Turkish tensions

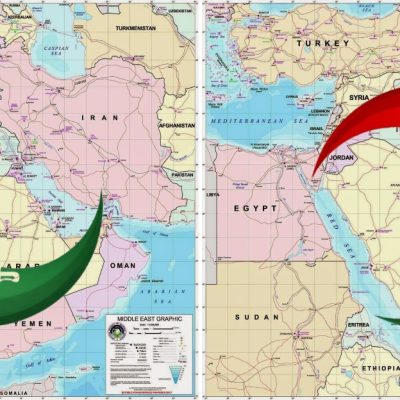

Spheres of influence and power relations are at the heart of the relationship between Moscow and Ankara. Their ambitions clash within an arc of crises that stretches from North Africa to the Caspian Sea via the Levant and the Black Sea.

The two countries have built a geo-economic partnership around energy projects linked to the gas and nuclear sectors. Partly submerged under the Black Sea, the Blue Stream pipeline has been supplying Turkey with Russian gas since 2003. In January 2020, its little brother Turkish Stream reached the markets of southern and south-eastern Europe via the Turkish port of Kıyıköy. And the Russian operator Rosatom is currently building Turkey’s first nuclear power plant for 25 billion dollars.

With 26.1 billion dollars of trade in 2019, the trade partnership also includes a form of complementarity in the tourist and agricultural domains. While 6.7 million Russian tourists visited Turkey in 2019, it will be the second largest importer of Russian agro-industrial products in 2020. Finally, its purchase of Russian S-400 anti-aircraft defence batteries illustrated the vitality of the military-industrial cooperation between the two countries, much to Washington’s chagrin.

Politically, Ankara and Moscow have a similar reading of world affairs, based on their common mistrust and frustration with the West, as well as a shared interest in a multipolar world order, which is supposed to allow them to assert their respective power projects. In this respect, their foreign policies have tended to become militarised in recent years, revealing a new disposition for the projection of forces.

Since the annexation of the Crimea in 2014, Russia is strengthening its military hold on the Black Sea. Turkey, as Master of the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits, has long played the role of a lock against Russian expansion into the warm seas. At knives drawn with Washington, Ankara and Moscow could now be able to keep the Western naval forces out of the area.

However, what might appear to be an anti-Western alliance is only a façade, as Ankara seems motivated by the desire to consolidate its positions vis-à-vis the Kremlin on the fronts in Syria, Libya and the Eastern Mediterranean. Turkey is feeling the pressure of Russia’s growing military footprint in its immediate neighbourhood, in the Black Sea, the Caucasus and the Levant. Ankara seems no longer to want to witness, powerless, the Russian military reinvestment.

Ankara could seek to acquire a military base in Azerbaijan to rebalance strategic relations with Moscow, which are perceived as unfavourable after Russia obtained in 2017 the bases of Tartous (navy) and Hmeimim (air force) for forty-nine years on the Syrian coast, on the nose and beard of Turkey.

Ankara has never recognised Russia’s annexation of the Crimea in 2014, without adopting sanctions against it. The Turks have extended their cooperation with Kiev in the military-technical field. In 2018, Ukraine placed an order for six Turkish Bayraktar-TB2 attack drones, the same as those used in Idlib (Syria), Libya and Nagorno-Karabakh. The new Bayraktar drone Akıncı could eventually be produced directly in Ukraine.

The reactivation of angry issues (Nagorno-Karabakh), the persistence of latent disagreements (Kurdish question, Donbass, gas issue in the Eastern Mediterranean) and the existence of open crises in which Russians and Turks profess antagonistic approaches (Syria, Libya) raise questions about the possible evolution of their relationship. To what extent is their current mode of operation likely to continue?

- The Lybian crisis

Since the popular uprising in February 2011 followed by the air intervention of NATO forces and the death of its head of state, Muammar Gaddafi, Libya has been plagued by chaos, fracture and external interference.

The Government of National Accord (GAN), recognised by the United Nations and whose political colour is similar to that of the Muslim Brotherhood, is supported by Turkey and more discreetly by Italy and Germany.

In the opposite camp, Mr Haftar, at the head of what he calls the Libyan National Army (LNA), is sponsored by Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and above all Russia, eager to increase its Mediterranean roots. We can also add France.

As a permanent member of the Security Council, however, Paris should stick to international legality by supporting the government of national accord, the only one recognised by the UN. Obviously, France is in opposition to Turkey, which has a strong presence in Libya.

While France denounces Turkey’s interference in the Libyan conflict, its support for warlord Khalifa Haftar explains why many Libyans reproach it for doing the same. Haftar has sold himself as a bulwark to jihadist groups.

Paris often expresses a certain intolerance towards political Islam and Islamic populism, which would explain among other things the fact of siding with Egypt and the United Arab Emirates.

France is trying to prevent the Syrian scenario from being repeated in Libya. The Turkish offensive in Syria in October 2019 targeted Syria’s Kurdish autonomist militias, allies of the West in the fight against terrorism. NATO had not reacted to condemn this Turkish operation, which was not concerted with the allies, but which had received the approval of Trump.

Given its security interest, the European Union, or NATO, would have to intervene. There was an urgency because the spectre of the establishment of jihadist movements and waves of immigration would appear this time, not in the Middle East but a few hundred miles from the European coasts. This would further weaken European cohesion, which is already quite fragile.

On the military level, Europeans are present at sea, whether in the framework of a European operation (IRINI) or NATO. On the one hand, there was control of the flow of immigrants, but above all control of the arms embargo on Libya. On various occasions, the operation’s ships have wanted to stop Turkish merchant ships bound for Libya for cargo control. On each occasion the merchant ships were accompanied by Turkish frigates which made control impossible. One of the Turkish frigates even engaged the French frigate “Le Courbet” on fire radar, an act considered extreme and incomprehensible between two NATO allies. This incident was a trigger for the escalation of tensions between France and Turkey in the summer of 2020.

In December, a German frigate (Hamburg) was controlling a Turkish merchant ship, everything went well but Turkey protested.

It should be noted that the European naval operation Irini off the coast of Libya is currently under the command of a Greek, which is rather amusing given the tensions between Greece and Turkey.

- Conclusions

The Russians are dealing with Turkey, which nevertheless supports the opposing camp. Ankara was an economic partner of the European Union and an ally of NATO but which posed a serious problem for both of them. This explains why this antagonism never translates into a brutal confrontation. A sort of contradictory alliance binds Mr Vladimir Putin and Mr Erdoğan. On Syrian and Libyan soil, their interests do not always coincide, but they give the impression of knowing how far both can go without exceeding a tolerable level of conflict.

In any case, the two partners RUS and TUR have the experience that would allow them to engage in bargaining based on compromise and compensation. Their acceptance of the logic of spheres of influence, Europe’s atony on strategic Mediterranean issues and America’s reluctance to embark on new military adventures provide them with additional room for manoeuvre to ensure that their interests coexist.

Like a marshmallow candy, Europe seems weak, a little soft, indecisive. But make no mistake about it. Once unity is achieved, it is very difficult to break the line. Ankara should therefore be wary. Russia, which had tried on several occasions to bend the decisions of sanctions that had hit it, was at its own expense. In spite of a few pitches, Europe remained on its feet. The economic sanctions that hit Moscow for its attitude in Ukraine have just been renewed. The same was true for the United Kingdom in the Brexit affair. For four years, the British leaders have tried almost everything to bend the European Union. Each time they have broken their teeth. And yet they had far more arguments than the Turks.

The Turks seem to want to return to Europe. Their warlike attitude is not sustainable in the long term because the Turkish President is finally isolated, he is in a cold war with the regional powers in the Middle East, interests with Russia are only facade and even within NATO, the European countries represent a certain weight, not to be underestimated at a time when the Biden Administration is again talking about multilateralism.

On the other side, Brussels needs Ankara. No matter the invasion of northern Syria and the installation of Islamist militias, no matter the repression against the Kurds in Syria, Turkey and Iraq, no matter the violation of the arms embargo in Libya, no matter the drilling in the eastern Mediterranean and the tensions with Greece and Cyprus or the dangerous incidents with the French fleet. Turkey wants to discuss the renewal of the migration pact with the EU. A formidable diplomatic weapon since Ankara is holding nearly 4 million refugees on its soil, a hypothetical wave of which haunts the nights of the European leaders.

In the same way, NATO could not lose this VIP member while Russia and China are ringing the doorbell.