On the afternoon of March 20, Royal Jordanian Airlines announced on Twitter that effective March 21, it would ban all electronic items from passenger cabins of its aircraft traveling directly to and from the United States with the exception of cellphones and medical devices. The announcement, which was later deleted from the airline’s Twitter account, noted that the security measures were being instituted at the request of “concerned U.S. Departments.” The U.S. government soon confirmed the ban and added that, in addition to Royal Jordanian, it applied to flights from eight other airlines originating from 10 airports in eight Middle Eastern countries.

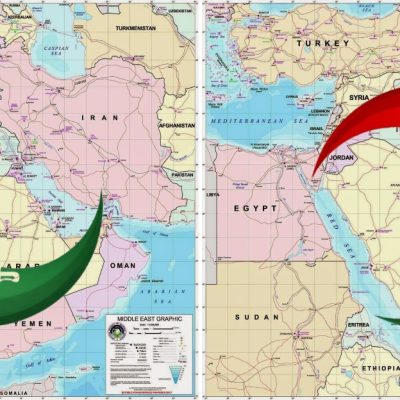

The airports covered by the ban are located in Cairo, Dubai, Abu Dhabi, Istanbul, Doha, Amman, Kuwait City, Casablanca, Jeddah and Riyadh. The airlines affected include Etihad Airways, EgyptAir, Qatar Airways, Emirates Airlines, Kuwait Airways, Royal Air Maroc, Saudi Arabian Airlines and Turkish Airlines. A U.S. Transportation Security Administration notice reportedly gave the affected airlines 96 hours to implement the new security measures. Noncompliance would result in their losing authorization to land in the United States. U.S. airlines were not affected by the measure because none of them fly from the affected airports to the United States.

The implementation of this security measure so abruptly is reminiscent of past U.S. aircraft bans. In August 2006, liquids were suddenly banned from aircraft passenger cabins in reaction to the discovery of a plot to use liquid bombs to attack U.S.-bound aircraft. Then in February 2014, all gels and liquids in carry-on luggage were banned on flights from Russia to the United States in response to intelligence pertaining to an alleged plot to smuggle explosives disguised as toothpaste aboard aircraft. Although Department of Homeland Security officials have been quoted in the press as saying there was no specific intelligence behind the ban, the manner in which it was instituted would seem to suggest that like past sudden changes, it is in reaction to recently obtained intelligence.

Some media sources have indicated that they believe the ban is politically motivated or some sort of protectionist measure intended to hurt Middle Eastern airlines, but on March 21, Reuters reported that the United Kingdom had instituted a similar ban, indicating that the measure is indeed based on security concerns. There are also reports that Canada will soon institute a similar ban.

Possible AQAP Connection

Some media reports are suggesting that this warning is connected to al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and its research to conceal explosives inside the batteries of electronic items. Given the group’s history of attempted attacks against U.S. aircraft — the 2009 underwear bombing attempt against Northwest Airlines Flight 253, the failed 2010 attack on a cargo aircraft using bombs hidden in computer printers, and a second underwear bomb plot with an improved device in 2012 — suspicion of AQAP is reasonable. Also, U.S. airstrikes have taken a heavy toll on the group’s leadership, giving it ample cause for revenge. AQAP also has the bombmaking tradecraft to construct such a device, and its bombmakers are known to have conducted extensive research on countering airport security screening measures. A report by ABC news indicates that fears about the Islamic States prompted the warning, but AQAP is a more credible suspect based on its past history.

In fact, AQAP may have been behind the sudden appearance of bombs concealed in laptop computers in Somalia in 2016. The group is tightly connected to Al Shabaab, which claimed the Somali attack last February against Daallo Airlines flight D3159. The blast killed the bomber and forced an emergency landing. A second bomb in a laptop computer exploded the following month at an airport in the Somali town of Beledweyne before it could be taken aboard the aircraft. These incidents could have been part of a test to gauge the devices’ effectiveness. And because the war in Yemen has stopped all flights from AQAP’s main operating area, it follows that the group might have coordinated with al Shabaab to test its laptop computer explosive devices.

This type of testing is not unusual and would be similar to an incident in December 1994 when a device hidden in a baby doll was tested on Philippine Airlines Flight 434. The baby doll bomb did not take down flight 434, and the plotters determined they needed to go back to the drawing board to create a more powerful device before widely deploying them against U.S. airliners in a wave of attacks named Operation Bojinka. The Daallo bomb in Somalia did not destroy that flight, and if it was a test it could have prompted some adjustments to the bomb.

Hidden Bombs

What isn’t speculation is that there is a long history of bombing attacks against aircraft. One reason is because relatively small quantities of explosives on an airplane can create a catastrophic incident that can kill all on board. It’s important to note, however, that as demonstrated by the examples of Philippine Airlines Flight 434 and Daallo 3159 — along with several others, such as Pan Am Flight 830 in 1982 and TWA Flight 840 in 1986 — airframes are more difficult to bring down than many people think.

Perhaps more important is the massive media attention that any attack against aircraft — even if unsuccessful — generates in the media, as have these new security measures. As we have discussed in the past, this level of media exposure serves as a significant terror magnifier, and past attacks against aircraft such as Pan Am 103, TWA 847 and the 9/11 attacks have become iconic images of terror.

The power of these images has created a fixation with attacks against aircraft that persists today. The attraction transcends ideologies — we have seen operatives of various ideological persuasions conduct terrorist attacks against aircraft, including Marxists, anti-Castro Cubans, Sikhs as well as North Korean and Libyan government agents. Jihadists have been plotting attacks against aircraft since the early 1990s.

Past attacks have resulted in security enhancements, which have themselves led creative bombmakers to change their methods of concealing bombs. An evolutionary arms race between bombmakers and aviation security officials has ensued. In addition to the methods of hiding explosives mentioned in the plots discussed earlier, past plots have involved explosives camouflaged in any number of ways, from TNT melted and casted into the shape of a tea set to explosives hidden in liquor bottles and shoes.

Electronics have long been a popular choice for bombmakers looking to smuggle improvised explosive devices aboard planes. Perhaps the most famous case is the Libyan-constructed device concealed inside a Toshiba radio cassette player that was used to bring down Pan Am Flight 103. Similar devices hidden in another model of Toshiba cassette player were found in a raid on a Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine-General Command safe-house in Germany a few months before the Pan Am 103 bombing.

In 1987, North Korean agents destroyed Korean Air Flight 858 using a modular explosive device design in which the firing train and a small charge of C4 were concealed inside a radio, which was then used to initiate the main charge of Picatinny Liquid Explosive hidden in a liquor bottle. In 1986, Nezar Hindawi, a Jordanian who later acknowledged working for Syrian intelligence, gave his unwitting and pregnant Irish girlfriend an IED concealed in a bag to take on an El Al flight from London to Tel Aviv. The timer and detonator for the device were concealed in a pocket calculator, and the main explosive charge was hidden in the suitcase under a false bottom. El Al security detected the device before it could be taken aboard the plane, and Hindawi was quickly arrested. One difference between the devices seen in Somalia last year and these earlier bombs is that the earlier devices used timers or altitude switches to detonate them. The laptop bombs in Somalia last year were command-detonated suicide devices.

Based on the stipulations of the new ban, this appears to be precisely the type of bomb it was intended to defend against, which suggests that there is intelligence that a militant group may have one or more devices of this type whose location is unknown.

One drawback of this type of specific warning is that it tends to focus attention narrowly on one type of concealment tactic, perhaps diverting the attention of security officers away from other forms of concealment and activation. Certainly if AQAP or another group did have such a device manufactured and was planning to use it in an attack against a U.S.-bound airliner, this ban will force the plotters to adjust, either by changing the method of concealment or by attempting to smuggle the device to another airport. Umar Farouk Abdulmutallab, the attacker in the failed 2009 underwear bomb plot, boarded his U.S.-bound flight from Schiphol airport in the Netherlands, and failed shoe bomber Richard Reid boarded American Airlines Flight 63 at Charles de Galle Airport in Paris, proving that attacks directed against the U.S. homeland don’t have to originate in the Middle East. Inevitably, if electronics are banned from aircraft cabins globally, attackers will simply seek a new method of concealment or a new way to detonate them in the cargo hold.

The Wider Implications

I see a close parallel between drug smuggling efforts and bomb smuggling efforts, and many of the methods mentioned above for camouflaging explosives have also been used for smuggling narcotics. As aviation security measures have evolved and adapted to drug smuggling efforts, narcotics “mules” have adapted as well, using everything from body cavities to drug-filled clothing to smuggle contraband.

This history of adaptive bombmaking and narcotics smuggling highlights the fact that it is impossible to use technical screening measures to absolutely prevent any explosive material from being brought on board an aircraft. Even prison authorities who can use magnetometers and strip searches to screen prisoners have failed to prevent all contraband from slipping through their system. And there is always the threat of items being introduced onto aircraft by ground crews, as may have been the case with Metrojet Flight 9268, which was destroyed by a bomb shortly after it departed from Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt, in October 2015.

Does this mean that all changes in air passenger screening are futile? No. At the very least, such measures prevent low-level threats from succeeding, and anyone who might have a device disguised in a laptop computer will have to take some time to retool.

But it also means that, given enough persistence and innovation, someone will eventually pass a device through the system. That next device might function better than the shoe bomb, the underwear bomb, or the Somalia laptop bombs — cases in which disaster was only narrowly averted. When the next attack happens, the public needs to maintain a realistic expectation of aviation security and not ascribe to the attackers some superhuman abilities or make totally unrealistic demands of passenger screeners that cost large amounts of money and still fail to guarantee security. The world is a dangerous place, and there are evil people who wish to commit atrocities against other human beings. Occasionally they succeed, but until that next happens, the arms race between bombmakers and aviation security officials will continue.