Original source: https://beta.theglobeandmail.com/news/world/move-fast-and-break-things-a-young-saudi-prince-is-upending-the-middle-east-is-he-playing-withfire/article36913721/?ref=http://www.theglobeandmail.com&

Inside Saudi Arabia, the agenda set out by Mohammed bin Salman, the young Crown Prince, is in motion. After last weekend’s sensational purge of princes and government officials, his power seems unchallenged, bolstering his credentials as the man who would modernize a patriarchal society and a sclerotic economy overly dependent on oil.

Outside Saudi Arabia, it’s a different story. Saudi Arabia and its arch-nemesis, Iran, are engaged in proxy battles that are marking parts of the Middle East map with bloodstains. In the past week, the tension between the two countries, which had been intensifying for years, turned potentially explosive. The trigger came when the Saudis shot down a ballistic missile they said had been fired by Iranian-backed Houthi rebels in Yemen. Iran was behind the “act of war,” the Saudis declared.

Prince Mohammed seems especially eager to restore his country’s influence in the Middle East. His war in Yemen, his blockade of Qatar and the surprise resignation a week ago of Lebanon’s prime minister and Saudi ally, Saad al-Hariri, indicate that the Prince is prepared to become highly aggressive in his offensive against burgeoning Iranian power. It is believed the Saudis forced Mr. Hariri’s resignation, which was made in Riyadh, not Beirut, because his coalition government has provided cover for the Iranian-backed Shia political party and militant group Hezbollah, which is part of his coalition.

The success of the Iranian-backed militias in Iraq, which have been fighting the Islamic State while spreading Iranian influence in the broken country, has surprised the Saudis. In neighbouring Syria, Iran has propped up the Assad regime. “We have foiled the American project in Iraq and on the Syrian borders, and we have succeeded in securing the road that links Iran, Iraq, Syria and Lebanon,” Jaafar al-Husseini, a spokesman for the Hezbollah Brigades, an Iranian-backed Shia force operating in Iraq, told The Associated Press.

On Thursday, Saudi Arabia instructed Saudi nationals to leave Lebanon immediately. Kuwait and United Arab Emirates issued similar statements. As the tensions ratcheted up, French President Emmanuel Macron set up an impromptu meeting with Prince Mohammed, saying it was essential to preserve “stability in the region.”

A day later in Beirut, Hezbollah leader Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah essentially went onto a war footing. In a TV address, he accused the Saudis of forcing the resignation of Mr. Hariri and detaining him, which he called an “unprecedented Saudi intervention” in Lebanese politics. “The most dangerous thing is inciting Israel to strike Lebanon,” he added. “I’m talking about information that Saudi Arabia has asked Israel to strike Lebanon.”

The Lebanon crisis did not seem to ruffle U.S. President Donald Trump. His only tweet came on Nov. 7, two days after Prince Mohammed’s purge and the resignation of Mr. Hariri. “I have great confidence in King Salman and the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia, they know exactly what they are doing,” he said.

Lebanon’s recently resigned prime minister Saad al-Hariri is seen at the governmental palace in Beirut on Oct. 24, 2017.

MOHAMED AZAKIR/REUTERS

Saudi Arabia no longer seems willing to see its influence in the Middle East wane. To help restore his country’s influence, Prince Mohammed has forged an unofficial alliance with Israel and Donald Trump’s United States against Iran. The question is whether the gambit will fail, triggering deeper conflicts that could destabilize Lebanon – where memories of the 1975-1990 civil war are still painful – and engulf the entire region.

Gary Sick, the senior scholar at Columbia University’s Middle East Institute who was a member of the U.S. National Security council under presidents Ford, Carter and Reagan, says Prince Mohammed’s foreign policy looks dangerous. “Almost everything could go wrong,” he said in a phone interview. “There is the potential for civil war in Lebanon. We are seeing a very different Saudi Arabia than we have seen before.”

In an article published Nov. 5 in Al-Monitor, only hours after Prince Mohammed’s purge, Bruce Riedel, a 30-year CIA veteran, senior adviser on the Middle East for the previous four presidents and, now, director of the Intelligence Project at Washington’s Brookings Institution, said Saudi Arabia is going through a particularly turbulent phase after decades of predictable and steady behaviour. “The kingdom is at a crossroads: Its economy has flatlined with low oil prices; the war in Yemen is a quagmire; the blockade of Qatar is a failure; Iranian influence is rampant in Lebanon, Syria and Iraq. … It is the most volatile period in Saudi history in over half a century.”

The rapid rise of Prince Mohammed has gripped the media in the Middle East and the West and shattered the sense of relative calm in one of the world’s last absolute monarchies. His modus operandi could well be: Move fast and break things.

Mohammed became deputy Crown Prince in 2015, when his father, Salman, was appointed King following the death of Salman’s half-brother, King Abdullah. At the time, King Salman’s Crown Prince – that is, the heir apparent to the throne – was Muhammad Bin Nayef, who is King Salman’s nephew and grandson of Saudi Arabia’s founding monarch, King Abdulaziz. That Crown Prince didn’t last long. In June of this year, he was ousted and, according to some reports, sent into house arrest, though he was finally spotted this week at a funeral of a prince who died in a helicopter crash. His replacement was Prince Mohammed Bin Salman, who is known as MBS in the West.

Prince Mohammed was already defence minister, minister of state and head of the Council for Economic and Development Affairs, which put him in charge of the ambitious attempt to reinvent the Saudi economy and wean it off oil – known as Vision 2030 – as well as having control over Saudi Aramco, the world’s biggest oil producer and potentially most valuable company as it heads to the stock market. On the weekend, Prince Mohammed consolidated his power through an extraordinary purge that was ostensibly an anti-corruption drive, and may well have been, but one with the pleasant (for him) side effect of eliminating some potential rivals.

The weekend’s night of the long knives, as it has been called, saw the arrest, detention or ouster of no fewer than 11 princes and about 40 government officials, including several cabinet ministers. The most prominent detentions were those of the Saudi billionaire investor Prince Alwaleed Bin Talal, whose holdings included Four Seasons, Citigroup and Twitter, and Prince Miteb Bin Abdullah, who had been head of the 100,000-strong National Guard, the only Saudi military force not under Prince Mohammed’s direct control. Prince Miteb was once a contender for the throne and was reportedly opposed to Prince Mohammed’s sprint to the top of the royal ranks.

By Thursday, 201 Saudis had been detained as part of a sweeping corruption investigation, with allegations that more than $100-billion (U.S.) had been lost to corruption and embezzlement, according to the Saudi attorney-general. Some 1,700 bank accounts have reportedly been frozen, a figure not confirmed by the attorney-general’s office.

One rumour says King Salman is bestowing Prince Mohammed with momentous power because he is preparing to abdicate, handing the throne to Prince Mohammed, who is only 32. If he becomes king, he could theoretically reign for 50 years.

The era of Prince Mohammed has arrived and all of the Middle East is on edge, trying to guess how he will curtail Iran’s expanding influence and what might get damaged along the way. “He’s very ambitious and sees Saudi Arabia as absolute leader in the Middle East,” Prof. Sick says. “He knows that Iran has been winning.”

But so far, the Prince’s efforts have come up short on the foreign front. His war in Yemen against the Iranian-backed Houthi rebels, who took control of the capital Sanaa in 2015, has bogged down, killing 10,000 people, half of them civilians, and spreading hunger and cholera throughout the country.

Prince Mohammed’s blockade of Qatar, which is diplomatically closer to Iran than Saudi Arabia, has failed to convince the Qataris to meet the Saudis’ demands, which included shutting down the Al-Jazeera news channel. If anything, the blockade has pushed Qatar closer to Iran. In Lebanon, the Saudis fear their vassal state is being overrun by Iranian proxies in the form of Hezbollah. Meanwhile, Saudi sponsorship of the rebels fighting Syrian President Bashar al-Assad has backfired. Mr. Assad, with the support of Iran and Russia, has reversed the rebel onslaught and, he claims, sent Islamic State packing.

Hezbollah supporters listen to a speech by Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah in Beirut on Nov. 10, 2017.

BILAL HUSSEIN/AP

Last year, Moshe (Bogie) Ya’alon, Israel’s defence minister from 2013 to 2016, called for Israel to join Sunni Arab states in an effort to contain Iran. “Israel and the Sunni Arab camp are in the same boat because we share common enemies,” he said in a Washington Institute policy forum speech. “Iran and its Shiite axis are a common enemy, and jihadists which are supported by specific Sunni states are a common enemy, and we have to work together to fight them. The USA must join us in supporting the Sunni Arab axis confronting Iran’s Shiite axis.”

Sayed Ghoneim, a retired Egyptian army major-general who is now chairman of the Institute for Global Security & Defense Affairs in Abu Dhabi, said in an interview that there is no doubt that “the Saudis and Israelis are working together to fight a common enemy” – Iran and its proxies. He does not rule out a regional war against Hezbollah.

Certainly the Saudis are using language to suggest that war is an option. In an interview this week with Al Arabiya, the Saudi TV service, Thamer al-Sabhan, the Saudi minister for Gulf affairs, accused Hezbollah of involvement in every “terrorist act” that threatened Saudi Arabia. “The Lebanese must choose between peace and aligning with Hezbollah,” he said.

The United States-Saudi alliance has been strong for years, but the Saudis found a serious backer of its anti-Iran stance in Donald Trump.

President Donald Trump is seen with Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman of Saudi Arabia during a visit to Riyadh on May 20, 2017.

STEPHEN CROWLEY/NYT

Riyadh was Mr. Trump’s first foreign visit after he became President. Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates donate $100-million (U.S.) to the Ivanka Trump-inspired Women Entrepreneurs Finance Initiative. Jared Kushner, Mr. Trump’s son-in-law, is close to Prince Mohammed. The Saudis have agreed to buy more than a $100-billion (U.S.) of weapons from the United States. Mr. Trump has called Barack Obama’s nuclear-abatement agreement with Iran “the worst deal ever,” even if he has stopped short of killing it.

The upshot is that the United States, along with Israel, has allied itself firmly with Prince Mohammed and his Sunni allies in the campaign against Iran and it proxies. How far that alliance is prepared to go is an open question. In the meantime, Prince Mohammed gives every indication that he won’t back down in his effort to restore Saudi Arabia’s pride and power in the Middle East. Lebanon, squeezed between the Iranian and Saudi adversaries, is not ruling out another civil war.

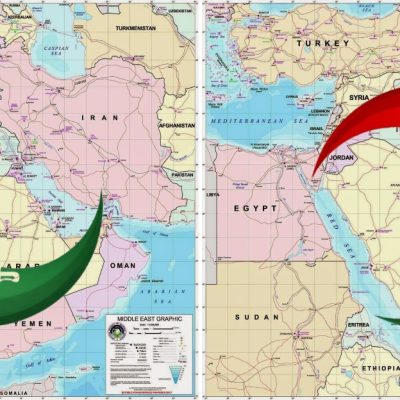

The Middle East: Who is in whose corner?

Saudi Arabia and Iran are the two powerhouses in the region and historic rivals. As the Middle East endured major wars and uprisings over the past 15 years, each side has poured money, arms and fighters into rival factions.

The Saudi corner

United States: The United States is by far Saudi Arabia’s oldest ally. The kingdom was the world’s second-largest importer of military equipment between 2012 and 2016, getting most of its weapons from the United States, according to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

Israel: When it comes to Iran’s nuclear and regional ambitions, Riyadh is aligned with Israel. Both see Iran as a regional threat.

Egypt: Riyadh backs Egypt’s President, Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi, who in turn supports the Saudi-led war in Yemen. But Egypt is opposed to war with Iran and Hezbollah.

Jordan: Like Saudi Arabia, it is a Sunni Arab monarchy with deep worries about Iran’s regional ambitions. King Abdullah II coined the phrase “Shia crescent” in 2004 – a warning that Iran’s influence was poised to extend across Shia populations in the Middle East.

The Iranian corner

Iraq: The U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003 and toppling of Saddam Hussein created an opening for Iran. It holds strong influence over the Shia-dominated government in Baghdad and Iranian militia were instrumental in crushing the Islamic State in Iraq.

Syria: In Syria, the ties of friendship with Iran go back to the 1980s, when Syria backed Iran in its war with Saddam Hussein. Today, Iran is backing the Assad regime with arms and fighters. Together, with Russian military help, they have defeated Islamic State in Syria.

Straddling both

Yemen: The deposed Yemeni president, Abed Rabbo Mansour Hadi, is central to Riyadh’s plan to restore Saudi influence to the south and stop Iran. The Houthi rebels, who belong to a branch of Shia Islam, seized control of the capital and have been the target of a relentless Saudi-led air war. The Saudis claim Iran is backing the Houthis.

Lebanon: In Lebanon, Saudi monarchs have backed the Hariri family. In 2005, prime minister Rafik Hariri was killed in a car blast. The militant group Hezbollah, which was created in Lebanon in the 1980s with Iran’s help to drive Israeli troops out of Lebanon, was blamed. Iranian-backed Hezbollah forms part of the current government, which was led by Saudi-backed Prime Minister Saad al-Hariri until he stepped down this month, fearing an Iranian plot to have him assassinated.